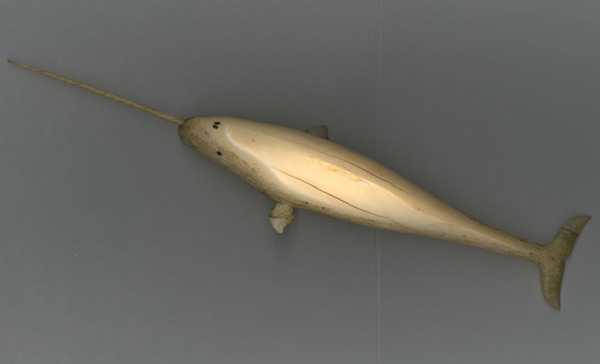

The Unicorn of the Sea

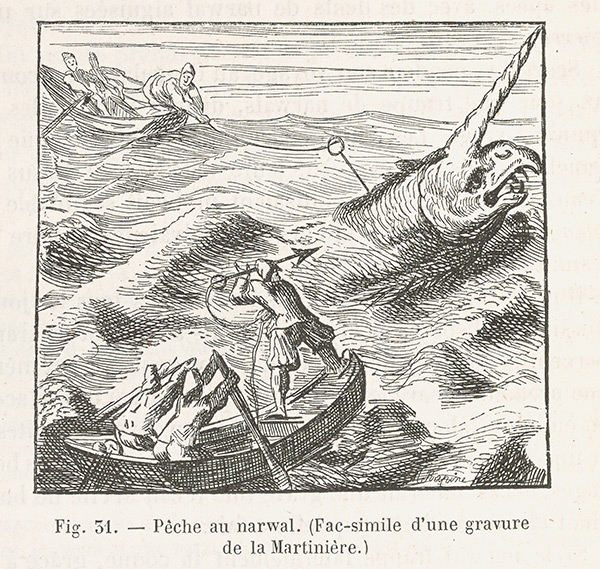

When Northern European sailors first caught glimpses of horned whales cresting the arctic waters in the Middle Ages, they were certain they had located the elusive unicorn. Some believed the animal had been hiding in the seas. Others saw this creature’s protruding feature as an opportunity to prove the existence of the mythical horned horse. Explorers and hunters returned to their cities with the impressive tusks as evidence. Compelled by stories of mystical powers, merchants sold the specimens for exorbitant sums. Queen Elizabeth I was gifted an elaborately decorated tusk of a “sea unicorn” from an explorer on her court. As the Age of Exploration dawned upon Europe, voyagers and natural scientists began to uncover more facts about this sea-dweller — a narwhal or narwhale. However, the powerful unicorn lore continued to hold great influence over research and public understanding. The stories that sparked frenzy across Europe retained their allure for centuries. The narwhal was featured in prominent 19th century works of fiction, including Herman Melville’s Moby Dick and Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. Unlike their mythical conflation, narwhals still traverse the arctic today and conservationists are working to protect the last living unicorn.

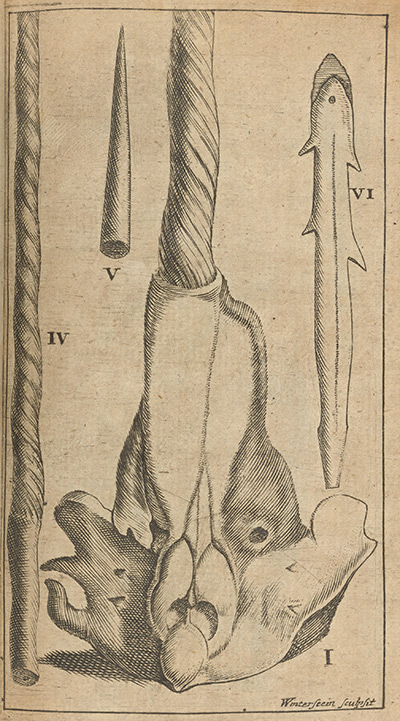

—“The Unicorn is but seldom seen in these parts […] I was informed, that he hath no finn on his back, as he is drawn […] When they swim swiftly in the water they say that they hold up their horns, or rather their teeth, out of the water, and so go in great shoals. The shape of their body is like a seal; the undermost finns, and the tail, are like unto those of the whale.”

—“Of the Unicorn” (Fourth Part of the Voyage into Spitzbergen), Frederick Marten, 1671. From An Account of Several Late Voyages & Discoveries to the South and North (London: Printed for Samuel Smith and Benj. Walford, 1694)

Special Collections, Providence Athenaeum